“The mythological layer confronts the stories and meanings humans apply to their surroundings. Stories that transform mere places into spaces of lived experience and imagination. Dr. Stephanie Leigh Batiste

The Origin of the Species

By Douglas Kearney

Based on from Sand and Sound: A Reference Guide to Desert Myths by Victor Wayne Graybrook

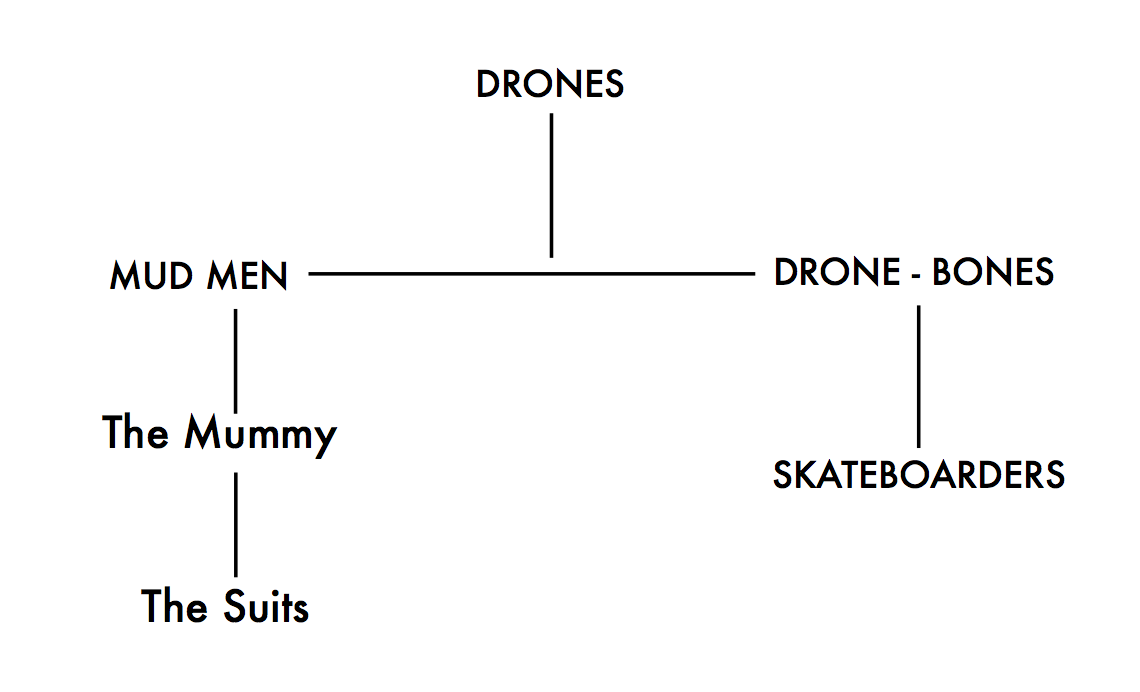

In this desert mythos, there is a clearly defined mytho-poetic understanding of human evolution. What follows is a sort of “family tree” diagram and explanation.

The Drones are the original race, existing before the desert fully formed. The sky had yet to even hold the sun. This “darkness” is easily metaphorized as an absence of a certain knowledge; however, it also may provide a comment of an internalized sort of knowledge. I’ll explain, we need light to see, that is, we need light to apprehend things physically outside of our selves. On the other hand, we require no light to see what we know or intuit. This may explain why even now, the Drones that inhabit another dimension (what we would call Mars) are considered an advanced species—perhaps the Drone mythmakers of our dimension were unaware that the sun affected Mars, too. We’ll discuss this more in the section on movement and time.

The arrival of the sun is still mysterious according to the mythmakers’ texts, yet, we can assume it introduced several key changes.

Light: By providing a view of a landscape and other organisms outside of each individual Drone, it created an understanding of difference and separation. The Drones understood that they were not the land. I would put forth the notion that the sun existed at this time purely as light—not yet as heat—and that the heat was perhaps a punishment that came later. Surely, in the light, the Drones would have been curious about “the Motherboard Rock.” Did they attempt to touch it, to carry it off, to damage it?

Heat: The burning sun enacts a typical motif of many myth traditions, the antagonistic separation of humankind from nature. The sun made it necessary for the Drones to cover themselves, which caused evolutionary/political splits within their culture. Thus, I read it as a punishment or at the very least a test. What is interesting to consider is whether the suits worn by the Suits represent a passing of the test, a failure or the test’s subsequent accumulation—its neutral result. Regardless, the heat led to the desert and the end of water as an abundant resource. The Drones understood water as a part of themselves (through saliva, semen, secretion, urine, tears and occasional sweat) and the earth. The interruption of this cycle first through the sighting of discreet water sources and through drought was surely devastating.

Evolution: The sun ultimately led to the evolution of the species. Drones were inadequately prepared for the intense heat and light of the sun. The species would have died out. However, they gained knowledge from an oversoul (which, for a society that had, at one point, a total internal knowledge may be best understood to us as memory)—This was the Ear. It is telling that this abstraction (memory) is concretized anatomically, yet specifically—an organ without sight! After all, sight was the cause of the trouble. The Ear’s ability to receive and transmit connect to the time of darkness, during which a Drone could hear itself breathing or its own pulse. The Drone’s ear is a part of that breathing and the receiver of that breathing. The Ear in the sky remembers precisely because it cannot see a material world. It aided the Drones by reminding several of them where they could find the water sources, now gone underground as a result of the heat. Yet, the question remains: did the Ear communicate to all of the Drones or a select few (a priest class)?

The Drones Evolve

The Mudmen are the Drones who heard and listened to the Ear, which taught them to use the water hidden/hiding in the earth to create a mud with which to protect themselves from the sun. This allowed them to keep living in the desert. It also enacts a reconnection with nature, the Mudmen immerse themselves in the earth, what’s more, they endeavored to grow even more closely connected. The earth spreads out before them, seeming not to move and yet always outpacing them in every direction they turned. They studied this unmoving motion and wondered wether it was the way to return to the state of not-seeing but knowing. Their vision quests were, in a sense, quests to escape vision. To move beyond ecstatic reverie into a sort of blindness. As earth would always be before them, distance became less important than movement.

Yet, what of the Drone-Bones? Are they failed figures like the andoumboulou or the Hebrew Lilith? Why are they not Mudmen?

Bones are interesting things. They are under our skin, similarly to how the water went under the ground; yet, they are a marker of death once exposed. The Drone-Bones appear after the Ear begins to transmit knowledge/memory to the Drones. It is unclear whether their appearance is simultaneous with that of the Mudmen. As bones are not likely to be revealed until after death, Drone-Bones are likely to represent those Drones who, for whatever reasons, failed—at least initially—to survive the coming of the sun. This is reinforced by the fact that Drone-Bones, when depicted, are always in a prone position—supine as though sleeping or dead. What’s more, they are always face-down. As mud was essential to such survival, we might assume the Drone-Bones either rejected or were not given the knowledge of how to properly use the mud. Either possibility goes some way toward explaining the idea of Drone-Bones as a lower species, classified as such either by their own stubbornness (face-down, they have turned away from the Ear) or by the Ear’s lack of favor toward them.

The Mummy

For this culture, evolution is often connected to acts of will. Either the Drones who became Drone-Bones refused the mud or the Drones who became Mudmen refused to give it to them. It is no surprise that the next step in evolution is also rooted in an act of defiance. The Mummy is a wholly unique figure in this mythopoetic tradition. She is the principal trickster (it may be a bit strong to consider her a cultural hero, except perhaps to the Drone-Bones, as we shall see). As do most tricksters, The Mummy occupies a space in transition—a bridge between Mudmen and Drone-Bones. She is associated with death (as are the Drone-Bones), yet she is preserved against death by a protective covering (as are the Mudmen). Her covering is made of cloth, seemingly developed when she distanced herself from the Mudmen’s wholly natural coating. Cloth, while composed of natural materials is a human-made product and represents a further movement away from nature. The Mummy eschewed the ethos of movement as consciousness and would often assume the attitude of the dead, laying prone as a Drone-Bone, face-down into the earth. There are several paintings of The Mummy in this attitude. I would encourage the curious to seek out copies of Ulrike Bergen’s series of pamphlets, “Der Mamaheld in der Ursprünglichen Kunst.”

According to the tradition, the Mummy may be responsible for saving the Drone-Bone branch of the species. The Mummy is associated with the first city built of the desert (which seems natural as the Mummy’s manufacture of cloth is the first example of craft in the mythology). Like the simple cloth covering, the desert-city is at once natural and synthetic. The Mummy consistently represents another level of separation between humans and nature. The Mummy is, thus, to the Mudmen, a transgressive figure.

The Desert-City Dwellers

The introduction of the desert-city created another schism within the species. Unlike the desert, which always outpaced the species no matter which way they could go, the desert-city ends when one reaches any area free of human manipulation. Thus, while it lacked formal borders—the walls and sheltering roofs we associate with our cities—there was a sense of spatial change that was on the one-hand desert, and on the other hand, not desert.

Finally, the species had a model for understanding the separation they felt upon the coming of light. The Mudmen that were willing to live in a hybridized organic/synthetic envronment remained in the desert-city and became Suits, further establishing tension with nature by wearing actual garments (versus the less refined bandages of the Mummy). Mudmen that refused the hybridization remained in the desert, trying to live a life without leaving footprints in the desert. Because of this, our information on them is very limited.

Drone-Bones that came to the desert-city had a similar evolution to undergo. Their time in the desert ended with a lack of desire to seek forgotten “knowing”—instead, they surrendered to (or were sentenced to) death attained with a lack of movement and subsequent fatal exposure to the heat. The desert-city dwelling Drone-Bones realized that their decision to live in the hybridized space was an act of will; yet, in order to perform their death, they needed witnesses. Again, these Drone-Bones sought, to eliminate their own will, to exist in a kind of virtual death. They surrendered themselves to the desert-city, spending most of their time prone as they did before in the desert. They decided to create a mode of movement that would be impossible in the desert. They constructed boards with wheels upon them. They lay prone on these boards and would move throughout the contours of the city, directionless and willing only to remain prone. Their will was negated as, though prone, they still moved without steering themselves, pressed by the slopes and angles of the desert-city. These became known as Skateboarders.

Movement and Time

We have already discussed how the Mudmen conceptualized movement. If all the world is a desert and the desert always outpaces you, distance was largely irrelevant to movement. What mattered was a connection to the earth (the ur-type elimination of separation/distance available to the culture). Without contact with the earth, movement was futile. The Skateboarders in the desert-city, further separated from the earth by their boards, enacted this principle. As the Suits grew more distant from the Mudmen and the earth, they lost their understanding of the ancient ways of Drones. The Ear in the Sky couldn’t be heard through the bustle of the desert-city, decaying the shared oversoul (“memory”). They remembered a distanceless traveling, the “walkabout,” and sought a way to recreate it in the desert-city. Yet, without contact to the earth, the concept of the “distanceless” was no longer connected to the principle of the limitlessness and concurrent everywhereness of nature. instead, distancelessness meant simply not going anywhere. The treadmill became the symbol of their misunderstanding. In construction, the treadmill is an inverse skateboard (driven perhaps by an ancestral memory to reject the Skateboarders). Inverse, in that the standing surface moves while the base remains still.

As the humans became aware of time only when the light separated (distanced) them from nature, Time and Distance became interrelated (again, the Mudmen staved off death by attempting a distancelessness). This would also explain why the Drones on Mars (distant) were, to the earthbound Drones, part of a visible future. Further, the Ear in the Sky transmitted past knowing to the Drones. This knowing, once a part of the bodies of the Drones was forced outside of them by the light. This knowing was memory and the Ear directed the Drones on where to recover these memories, these bits of once internalized nature. Thus it is said

“The Desert Whispers and the Ear Hears.”

One must consider that this is an anatomical metaphor, the Desert and Ear are part of a continuum, rather, a single unit, just as you can hear yourself breathing. The saying, therefore was not an observation, but an imperative. Only the desert can speak—the humans had to become one with the Earth again to possess the memory; and only the Ear—the state of knowing, not seeing—can recall these memories.

Thus, the Motherboard Rock becomes the central site of recovering ones connection/memory. It is unclear whether the Motherboard Rock is a specific sacred site or synecdoche for the Earth itself. What we do know of the culture’s ritualistic practice is the suggestion that one reaches the Motherboard Rock through death—similar, perhaps to our “ashes to ashes and dust to dust.” Whether this is a death that can be simulated—a kind of Good Friday; a kind of hibernation and fasting; or a journey to an actual underworld of caverns is unclear.

Hunger? Awe? or Song?

Many images of the species depict them with their mouths agape. It has long been theorized that this illustrated hunger/thirst. The vacancy of an open mouth suggests a space to be filled. It is of course tempting to consider the desert as a barren place and, as such, a source of unfulfilled desire.

Dr. Nicole McJamerson, in her paper, “Ah/Awe: Representing the Sublime in the Stylized Image,” added to the dynamic of desire, the power of awe. The suggestion being that the culture suggested a kind of constant recognition of a greater power. It might be presumptuous to compare that with our own systems of “living in prayer”; yet, perhaps it is a useful if temporary parallel. Yet, my own research offers another possibility. What if the open mouth is there to represent singing? That a group of these beings united in song, imitate the Ear in the Sky which transmits and receives? I find it compelling that this particular mode of communication does requires neither sight nor writing surfaces. Further, we have examples of song being associated with distances in our own history. Australia’s Aboriginal culture—also desert-dwelling—believed song was necessary for effectively moving throughout the continent. I quote Bruce Chatwin’s SongLines, here “Sometimes, I’ll be driving my ‘old men’ through the desert, and we’ll come to a ridge of sandhills, and suddenly they’ll all start singing … what are you mob singing? … ‘Singing up the country, boss. Makes the country come up quicker.’”

While there is still much to learn about this particular culture, it is encouraging to note that interest in the field is expanding. We can only hope that through the recovery of more texts and images met with the most scrupulous research, we may learn that indeed there is ultimately one desert and through examining our diverse ways of walking, reading and I daresay, singing these austerely beautiful seas of sand, perhaps we can learn more about ourselves and each other.